Promises vs Provision: Public funding for NEP 2020 stuck at around 4% of GDP

Team Careers360 | September 16, 2025 | 10:07 AM IST | 18 mins read

5 years after NEP, India’s education spending stagnant at 4.1% of GDP while declining scholarships, fund shift towards elite institutes, and rising student debt challenge its vision of inclusivity

By Protiva Kundu

India has one of the largest education systems in the world, with over 26.5 crore students enrolled in 15 lakh schools and 4.3 crore students across 59,000 higher education institutions. Over the past five years, India’s education system has witnessed substantial structural changes, many of which are still in progress.

While the ultimate shape and impact of these reforms remain to be seen, the scale of transformation is undeniable. In this context, public financing plays a foundational role. A system of this magnitude and diversity cannot achieve inclusive, equitable, and quality education outcomes without adequate and sustained public investment.

Public spending on education

In policy discussions around government financing of education, two recurring questions dominate: (i) How much does the government spend on education? (ii) Is the current level of spending adequate to ensure quality education for all?

To answer the latter, an assessment of adequacy must be grounded in an estimate of the required investment for delivering quality school education. This exercise in estimation began with the Kothari Commission (1966), which, after comprehensive analysis, recommended that public expenditure on education should reach 6% of the Gross National Product (GNP) by 1985–86, with at least two-thirds allocated to school education during the first few decades. This benchmark was reiterated by the National Policy on Education (1986) and subsequent expert committees, including Saikia Committee (1997), Tapas Majumdar committee (1999), CABE committee (2005). Following the Right to Education (RTE) Act, 2009, National Institute of Educational Planning and Administration (2009) estimated that an additional Rs 1.7 trillion was needed for its implementation by 2015.

Despite these recurring assessments, India’s public expenditure on education has consistently fallen short of the 6% target. In this discourse, the recent addition is National Education Policy (NEP) 2020. The policy has acknowledged the need for higher investment in education and envisioned that to reap maximum benefits from this investment, financing should be largely from public sources. However, in line of the previous education policies, NEP 20201 confined its recommendation only to public spending of 6% of GDP for education “at the earliest”.

One of the fundamental challenges in assessing the current size of the public education resource envelope is the lack of timely and updated data on education financing. Accurate and current information on how much the union and state governments are spending on education is often not readily available. While the ministry of education’s annual publication — Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure on Education (ABE)2 — provides a comprehensive overview of public education spending, it is released with a considerable time lag.

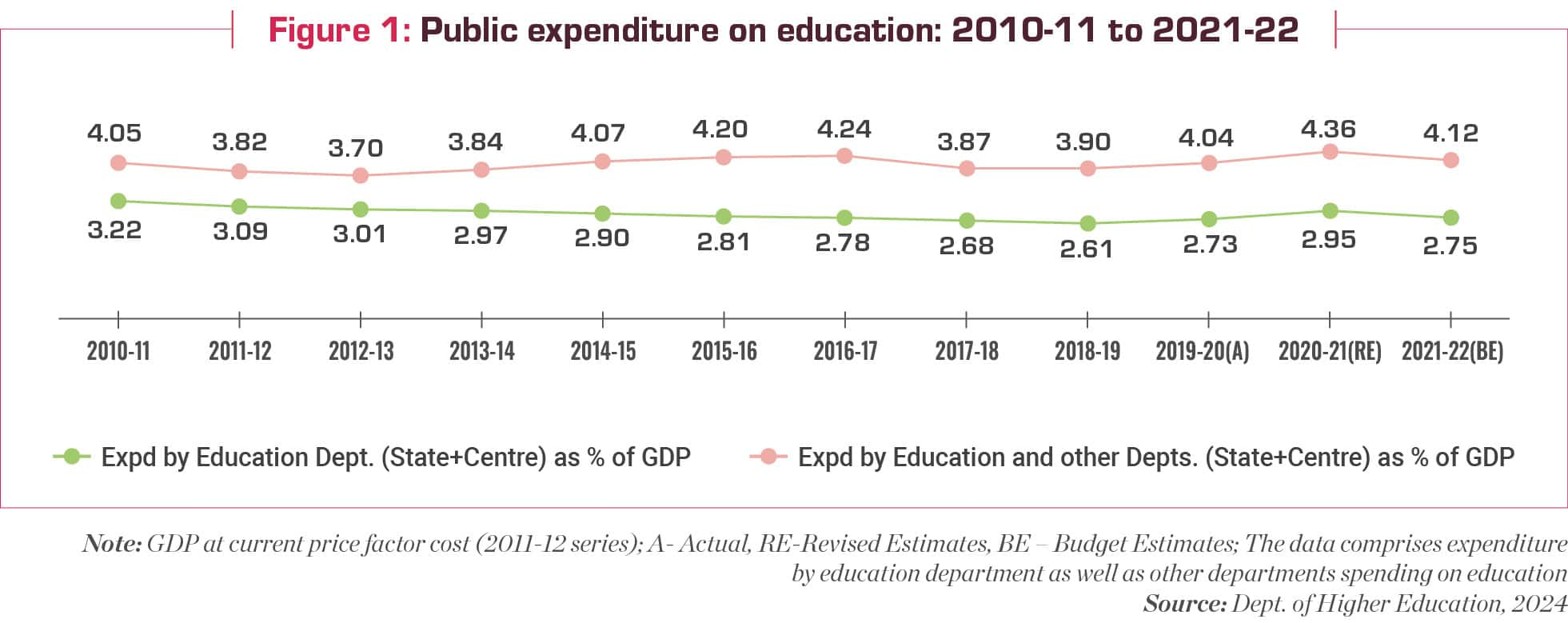

Public expenditure on education as percentage of GDP over 10 years

Public expenditure on education as percentage of GDP over 10 years

The latest available edition, ABE 2021–22, shows that till 2021-22 (BE), centre and states together had allocated 4.1% of GDP on education, much short of the benchmark recommended by the Kothari Commission 40 years ago.

It is also important to remember that the 6% figure is by no means excessive in comparison to many other developing countries, such as South Africa and Brazil3.

Only about one-third of this total spending was routed through the Department of Education, a sharp decline from nearly 80% in 2010–11 (Figure 1). Other than the ministry of education, around 48 ministries/ departments spend on education and training in India. The top five of these are the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Ministry of Women and Child Development, Department of Atomic Energy, Ministry of Defence and Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment.

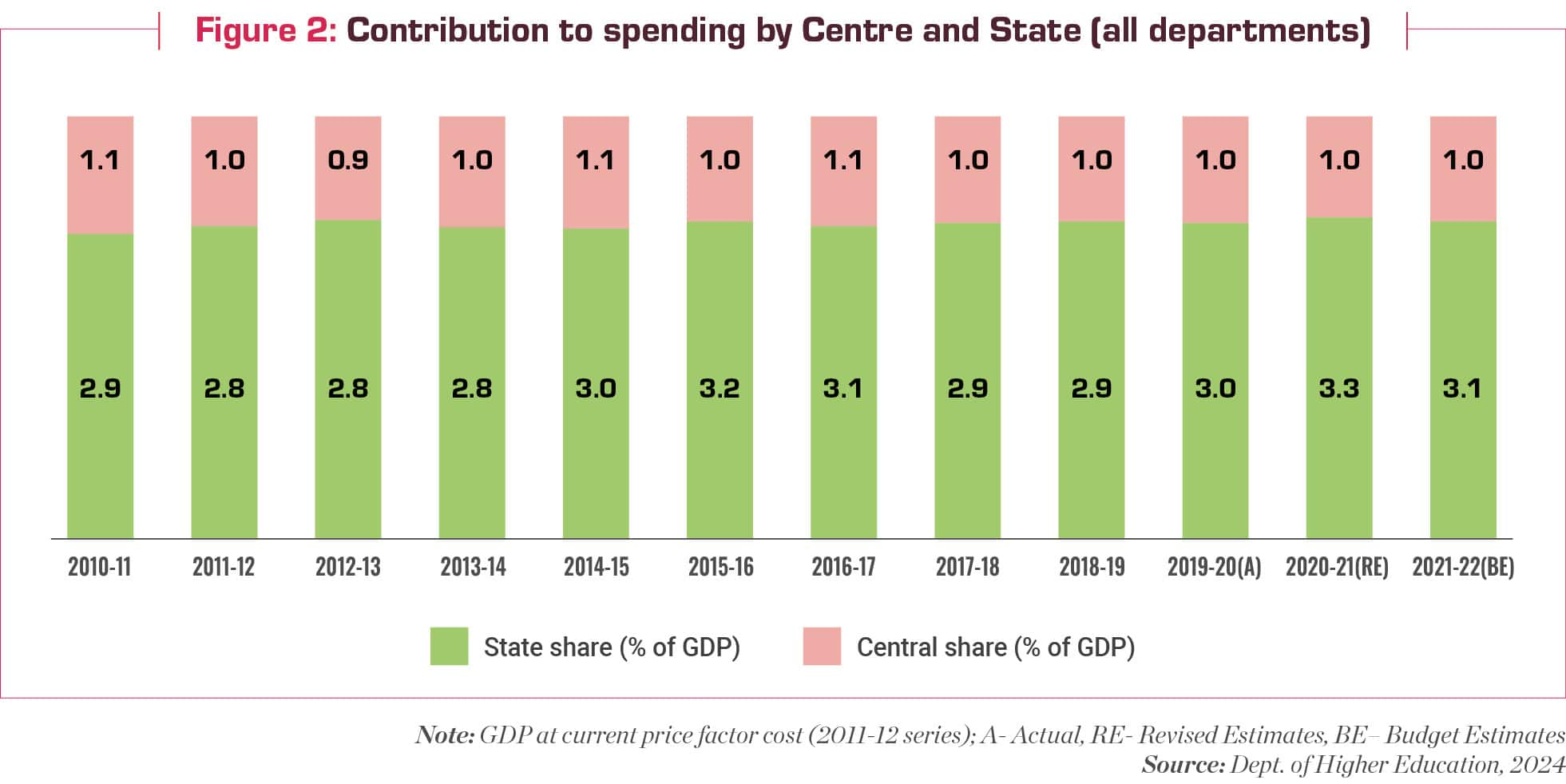

The trend in education financing, particularly in the composition of union–state resource sharing, reflects a gradual shifting of financial responsibility away from the union government, despite education being placed in the Concurrent List of the Constitution, which mandates a shared responsibility between the centre and the states.

Spending on Education: Centre and state contributions

Spending on Education: Centre and state contributions

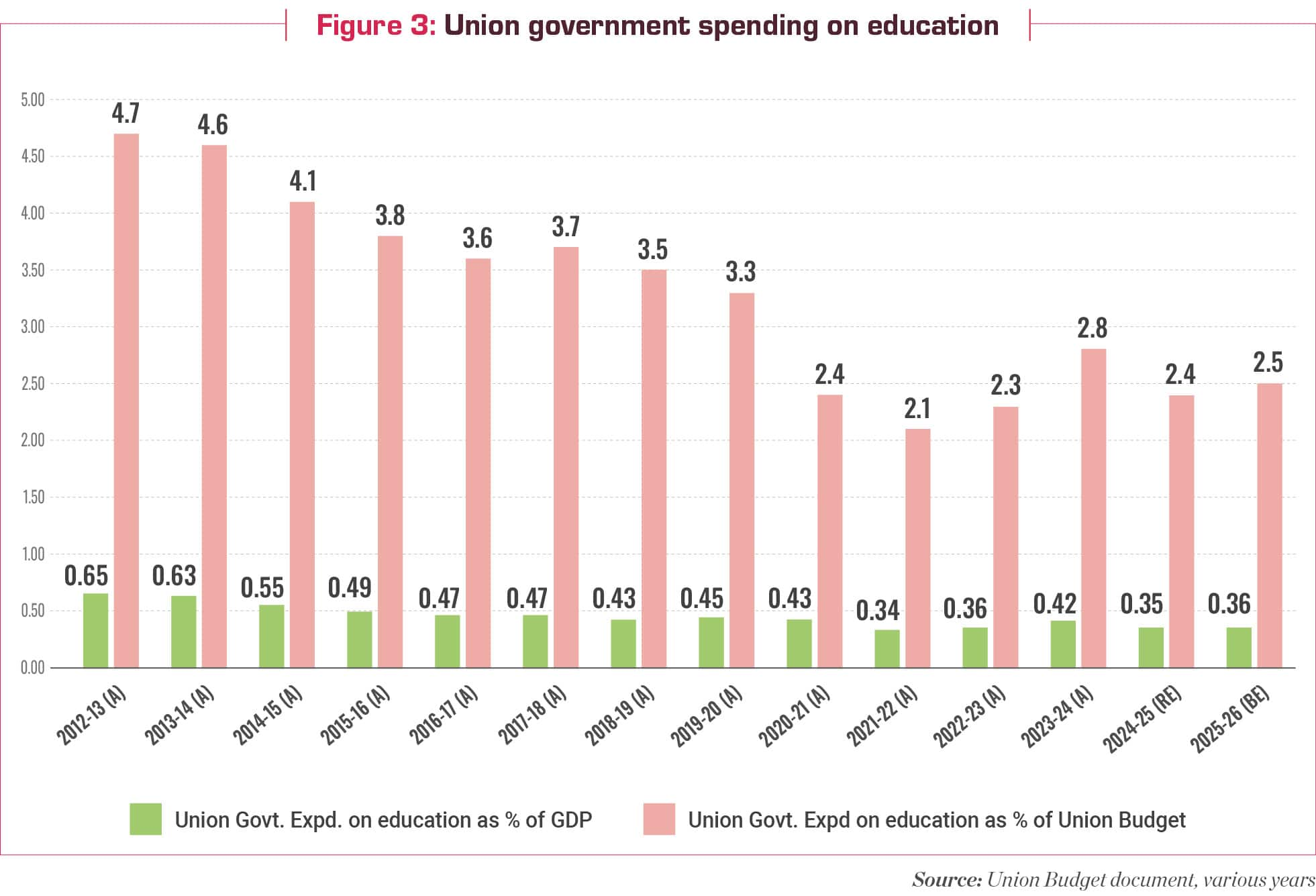

Successive Union Budget speeches over the last few years have spotlighted education, skill development, and job creation as key pillars for empowering youth. However, the actual trajectory of policy decisions and financial allocations to the ministry of education over the periods does not fully align with these stated commitments. Though the education budget has increased in absolute terms, its share in total government expenditure is continuously decreasing.

A similar picture is observed when the education budget is compared with the country’s GDP (Figure 3). This reduced priority is also highlighted in Economic Survey 2024-25, which shows that of the 8% of GDP spent on the social sector, 36% goes to education as a combined allocation by Centre and States in 2024-25 (BE), which was 41% in 2016-1744.

Union government spending on education

Union government spending on education

Though the survey has attributed this reduction in social sector expenditure to limited fiscal space of the governments, a state-level analysis shows that during the first four years of the Fourteenth Finance Commission period (which ended in 2019-20) many of the states actually increased their expenditure on the social sector, including education (Save the Children-NCE, 2018).

School Education: Shifting priorities, stagnant commitments

India’s school education system is one of the largest in the world, serving 24.8 crore students across 14.72 lakh schools, with a teaching workforce of nearly 98 lakh teachers. Government schools constitute 69% of all schools, enrolling 50% of students and employing 51% of teachers5.

NEP sets an ambitious goal of achieving a 100% Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) across all levels of school education by 2030. While the GER for elementary education is 92.7, secondary education remains far from universal. According to ASER 2024, dropout rates are especially high among marginalised groups: 12% for SC girls and 15% for ST girls. Transition from elementary to secondary levels shows a continuum in the gender gap, exacerbated by poverty, poor infrastructure, and lack of targeted incentives.

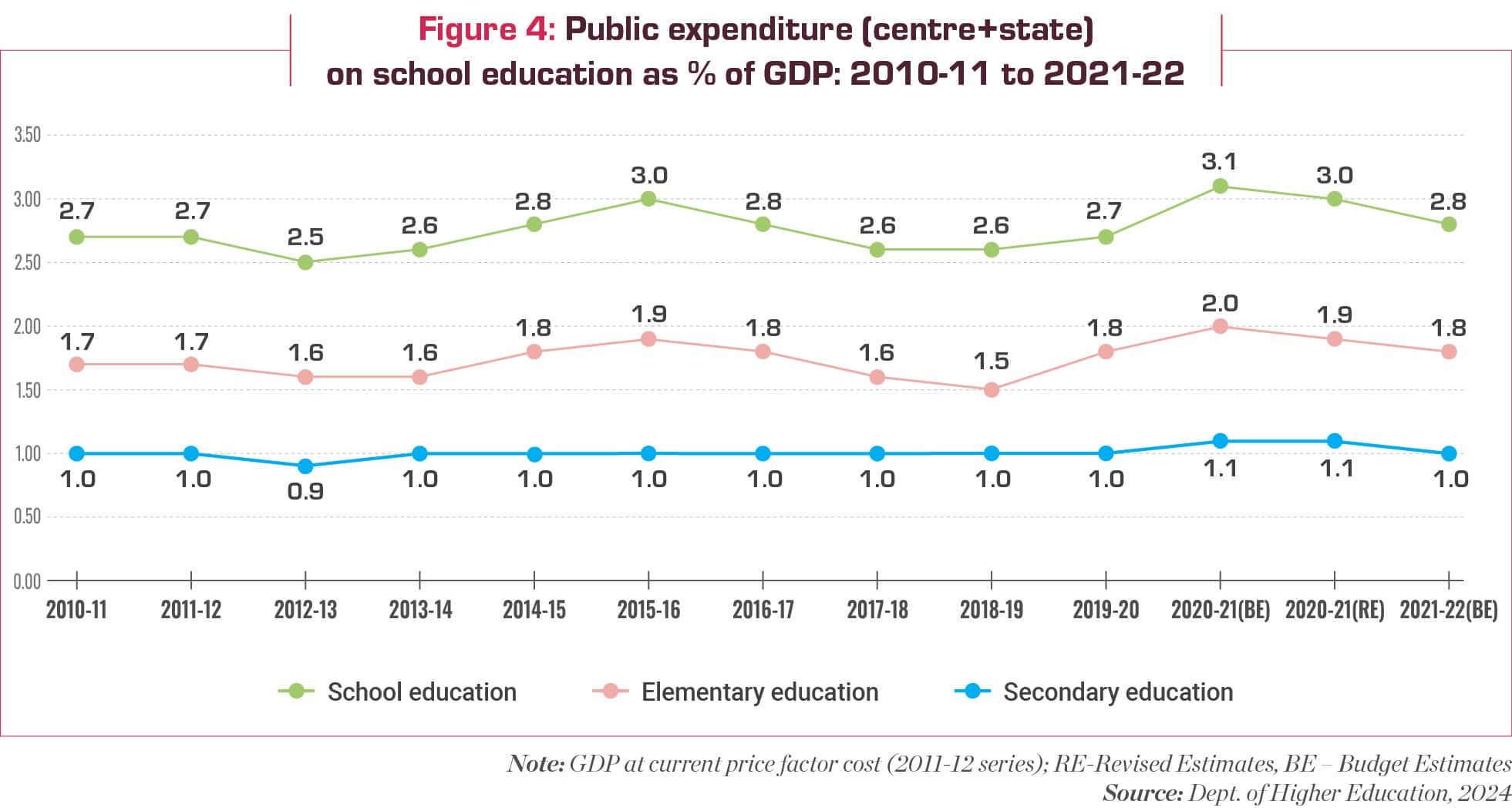

NEP underscores the need for robust public investment, system strengthening, and inclusive reforms to meet the scale. However, it does not offer a clear financing strategy to mobilise the necessary public resources required to fulfil these commitments. As of 2021-22 (BE), public spending on school education stands at 2.8% of GDP, reflecting a marginal increase of only 0.1 percentage point over the last decade. Nearly two-thirds of this spending is directed towards elementary education. While the demand for secondary education rises with the expansion of elementary education, the expenditure on secondary education has remained stagnant at 1% of GDP for the past 10 years.

Expenditure on school education as % of GDP: Centre and state

Expenditure on school education as % of GDP: Centre and state

The current 2.8% of GDP allocated for school education, which amounts to Rs 6.6 lakh crore in absolute terms or Rs 38,866 per student per annum, is certainly not a small amount. However, it is important to note here that Kendriya Vidyalayas, which are considered ‘model’ schools financed by the Union Government, spent around Rs 50,314 per student in 2021-22.

Underutilisation of funds, over-reliance on education cess

While the union government bears only 25% of the school education expenditure, the chosen means of financing school education and system level reform are largely through schemes and programmes for a longer period of time. These include Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SMSA), PM Poshan/Mid day Meal, National Means cum Merit scholarships.

In the middle of 2018-19, Government of India launched Samagra Shiksha Abhiyan (SMSA) integrating Sarva Shiksha Abhiyan, Rashtriya Madhyamik Shiksha Abhiyan and Teacher education. It was expected that there would be a big-push of resources for SMSA in the Union Budget 2019-20.

However, like SSA and RMSA, the SMSA remains severely underfunded from its very inception. The under-allocation is glaring compared to what MoE has committed to allocate as central share for SMSA to States.

Major changes from NPE 1986 to NEP 2020 in school education |

|---|

|

Parliamentary Standing Committee reports (2021–23) consistently point to gaps between projections, allocations, and actual expenditure incurred under SMSA (Table 1).

Projection of funds made, allocated and spent on SMSA by Union government (Rs crore) | |||

Year | Fund approved | Funds allocated | Expenditure |

2018-19 | 34,000 | 30,892 | 29,015 |

2019-20 | 41,000 | 36,322 | 32,377 |

2020-21 | 45,934 | 38,750 | 27,835 |

2021-22 | 57,914 | 31,050 | 25,061 |

2022-23 | 38,825 | 37,383 | 32,515 |

2023-24 | 37,985 | 37,453 | 32,830 |

2024-25 | NA | 37,500 | 37,010 |

2025-26 | NA | 41,250 | - |

Note: NA- Not available, 2024-25 expenditure data is revised estimates. Source: Department related Parliamentary standing committee report, Dept. of School Education and Literacy, various years

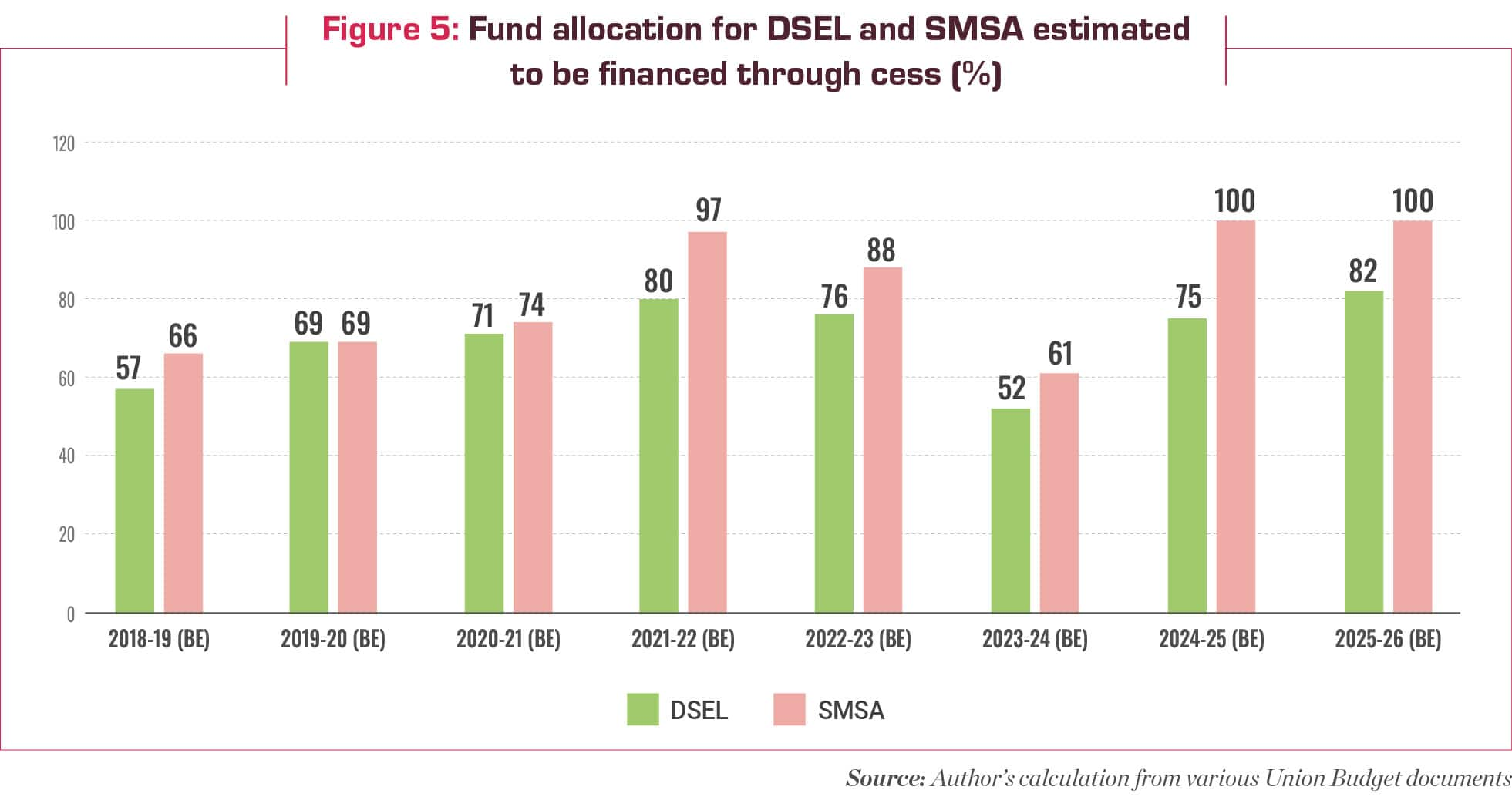

Moreover, school education continues to be financed predominantly through education cess. Originally introduced to supplement public investment in education, the education cess was envisioned as an additional resource stream, not a replacement for core budgetary support.

The department of school education and literacy receives proceeds from this cess, which is levied on all central taxes and customs duties, and is channelled into non-lapsable funds known as the Prarambhik Shiksha Kosh and Madhyamik and Uchhatar Shiksha Kosh. However, over the past decade, a significant share of government financing for school education has been routed through the education cess, rather than from the core budgetary allocations (Figure 5). This pattern of financing raises concerns about the sustainability and predictability of education financing.

Budget for SSA, DSEL funded through education cess

Budget for SSA, DSEL funded through education cess

Financing the few

A notable re-prioritisation of funds is witnessed in the budgetary allocation of the Department of School Education and Literacy (DSEL). Between 2019–20 and 2025-26, the share of SMSA — the umbrella programme for school education — declined from 62% to 51% of the DSEL budget. In contrast, the share of exemplary schools, including Kendriya Vidyalaya, Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalaya and PM Shri schools, rose sharply, from 19% to 29%, though they serve a relatively small number of students.

The disproportionate increase in allocations to Eklavya Model Residential School — serving mostly ST students—is often cited as a push for inclusive excellence. At the same time Kasturba Gandhi Balika Vidyalaya, residential schools for marginalised girls, set up with the same purpose are resource starved. This trend reflects a growing emphasis on a few showcase institutions at the expense of mass provisioning. Moreover, targeted interventions for Scheduled Caste (SC), Scheduled Tribes (ST), and minority students are either underfunded or inconsistently prioritised. In spite of increased demand for scholarships, the budgetary allocation for pre matric scholarships for SC, ST and minorities witnessed substantial budget cuts in the last few years. None of the states has created a gender inclusion fund as suggested in the NEP. Such an approach contradicts NEP’s vision of an equitable and inclusive school education system.

A recent study6 by the Centre for Budget and Governance Accountability (CBGA) and child-rights NGO, CRY evaluating four years of NEP 2020 implementation in school education across six states finds that the progress has been uneven, politically nuanced, and remains at a nascent stage; while some states have adopted the policy with significant enthusiasm and contextual modifications, tailoring it to the state-specific needs, a few states have formally rejected the policy. The study also found that despite increased fiscal devolution under the 15th Finance Commission, state investments in education remain inconsistent.

Public financing of higher education: A reality check

NEP 2020 sets an ambitious target of achieving a 50% GER in higher education by 2035.

Over the past two decades, India has made steady progress toward this goal, with the national GER rising from 8.07% in 2000–01 to 28.4% in 2021–22. While this upward trend is encouraging, the current GER remains low both in comparison to global standards and within the Indian context, where significant interstate disparities persist. For instance, in 2021–22, Tamil Nadu and Delhi had already achieved a GER of 49% for the 18–23 age group — nearly reaching the NEP target. In contrast, states like Assam (16.9%), Bihar (17.1%), and Jharkhand (18.6%), as reported in the All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2021-22, lag far behind. These regional inequalities point to structural challenges in access, affordability, and institutional capacity and underscores the critical need to strengthen public provisioning for higher education.

Major changes from NPE 1986 to NEP 2020 in higher education |

|---|

|

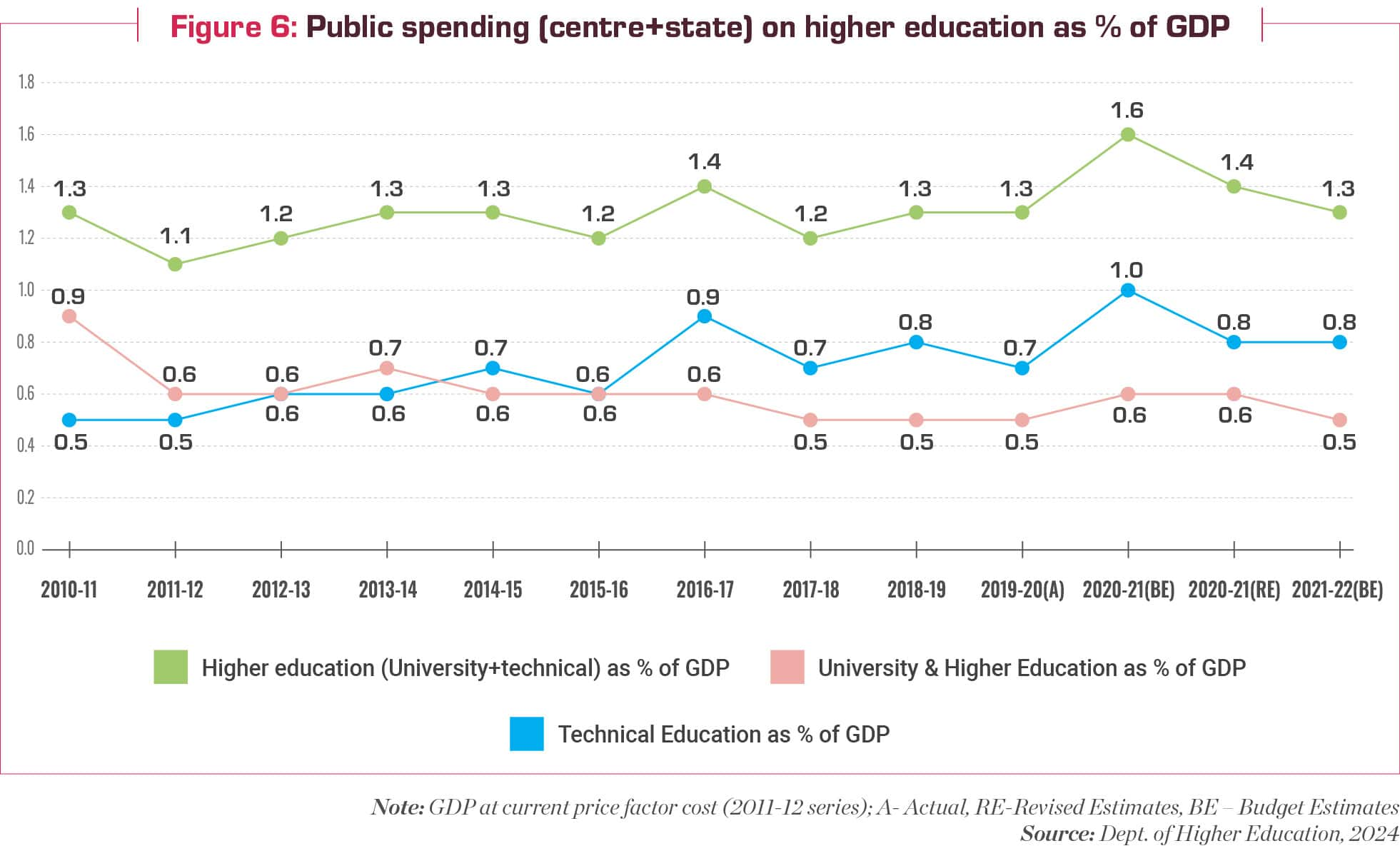

According to the latest available data, for the last 10 years total public spending on higher education in India is more or less stagnant at 1.3% of GDP. During this period, expenditure on university and higher education declined from 0.9% to 0.5% of GDP, whereas spending on technical education surged from 0.5% to 0.8% of GDP — a 60% increase (Figure 6).

Centre and state government spending on higher education as % of GDP over 10 years

Centre and state government spending on higher education as % of GDP over 10 years

This shifting priority within the composition of spending — with a marked tilt towards technical education clearly is at the expense of general university education. At the Union level, around 40% of the Department of Higher Education budget goes to premier institutions such as IITs, IIMs, IISc, and AICTE. The shift reflects a strategic tilt towards market-oriented and employability-driven sectors, but also raises important questions about equity and the inclusive development of the higher education sector, particularly since over 70% of students are enrolled in non-technical, general degree programmes at local and regional institutions.

Exclusion in the name of excellence

In case of university and higher education, much of the central government’s budgetary allocation is for central universities. While centrally funded institutions are considered better in terms of quality, they still remain as islands of excellence, catering to the knowledge requirements of a selected few. The NEP 2020 strives to establish an unparalleled education system in India by 2040, ensuring access to top-tier education regardless of social or economic background. This has been reflected in policy shifts towards internationalisation of higher education institutions, named “world class institutions” or “institutes of eminence”, with greater government funding and visibility.

On the other hand, while the state universities and colleges cater to a large number of students, their funding by the central government is only a fraction of that provided to central institutions although the goals are set by the Union Government. Over the years, most states have not been able to allocate enough funds to higher education as a significant portion is absorbed by salaries and pensions, leaving minimal fiscal space for infrastructure and capital investments.

The University Grants Commission (UGC), which plays a central role funding universities and colleges across India through grants-in-aid, funds for infrastructure development, faculty training, research projects, and student welfare schemes, has witnessed significant budget cuts in the last five years. According to a recent report, Delhi University is grappling with a mounting financial crisis, with its projected deficit for the financial year 2025–26 touching a staggering Rs 462.4 crore — a sharp 86% rise from last year’s shortfall7.

It is to be noted here that a vast majority of higher education institutions are not even eligible to receive any kind of grants from the UGC. As per UGC annual report 2023-248, out of 1,153 universities, 47 central universities, 161 State Public Universities and 29 State Private Universities, 409 private universities and 61 deemed to be universities are eligible to receive grants from the UGC.

Funding continues to fall short of the projected needs for centrally-sponsored schemes, like Rashtriya Uchhatar Shiksha Abhiyan (RUSA but renamed PM-USHA), even though they are intended to support states in aligning with NEP goals, but funding continues to fall short of the projected needs.

HEFA: Shifting landscape of higher education financing

The introduction of the Higher Education Financing Agency (HEFA) in 2016 marked a significant shift in the financing model for infrastructure development in higher education. Instead of direct capital grants, public institutions were encouraged to take loans from HEFA to fund infrastructure projects—signalling a move from public provisioning to loan-based financing.

Despite its ambitious vision of mobilising Rs 1 lakh crore by 2022, HEFA fell well short of this target. As of March 2025, it had sanctioned Rs 43,437.6 crore and disbursed Rs 22,600.8 crore in loans, covering 109 premier institutions, including IITs, IIMs, NITs, AIIMS, and central universities9.

Following the launch of HEFA and the RISE10 initiative, there has been a marked reduction in capital grants from the Union Government, even for institutions with ongoing and incomplete infrastructure projects. As a result, institutions are now required to repay their loans using their own internal revenue, which has placed a significant strain on their financial sustainability. For example, IIT Delhi reportedly dedicates around 50% of its internal revenue to servicing HEFA-related debt. Similarly, Delhi University is expected to pay nearly ₹93.8 crore in interest alone to HEFA in the financial year 2025–26.

Also read NITI Aayog suggests HEFA-like agencies, fee hike, self-financed courses for state universities

To bridge the resource gap, institutions continue to hike student fees to increase internal revenue and repay loans. This raises concerns about accessibility and affordability for students. However, for the last few years, the Union budget for student financial aid either remained unchanged or witnessed a budget cut, which adversely affected students, especially those from socio-economically marginalised groups and dependent on public provisioning of higher education.

Increasing cost; dwindling support for scholarships, fellowships

Equity remains a critical gap in higher education. The trends in higher education financing in India show a decline in targeted funding mechanisms, such as scholarships and fee reimbursements, even as enrolments from disadvantaged groups are rising.

The NEP 2020 envisions enhanced scholarships and financial support — including through private and philanthropic institutions. Although several scholarship schemes currently operate in India, the combination of rising enrolment and declining budgetary allocations has weakened the effectiveness of these programmes.

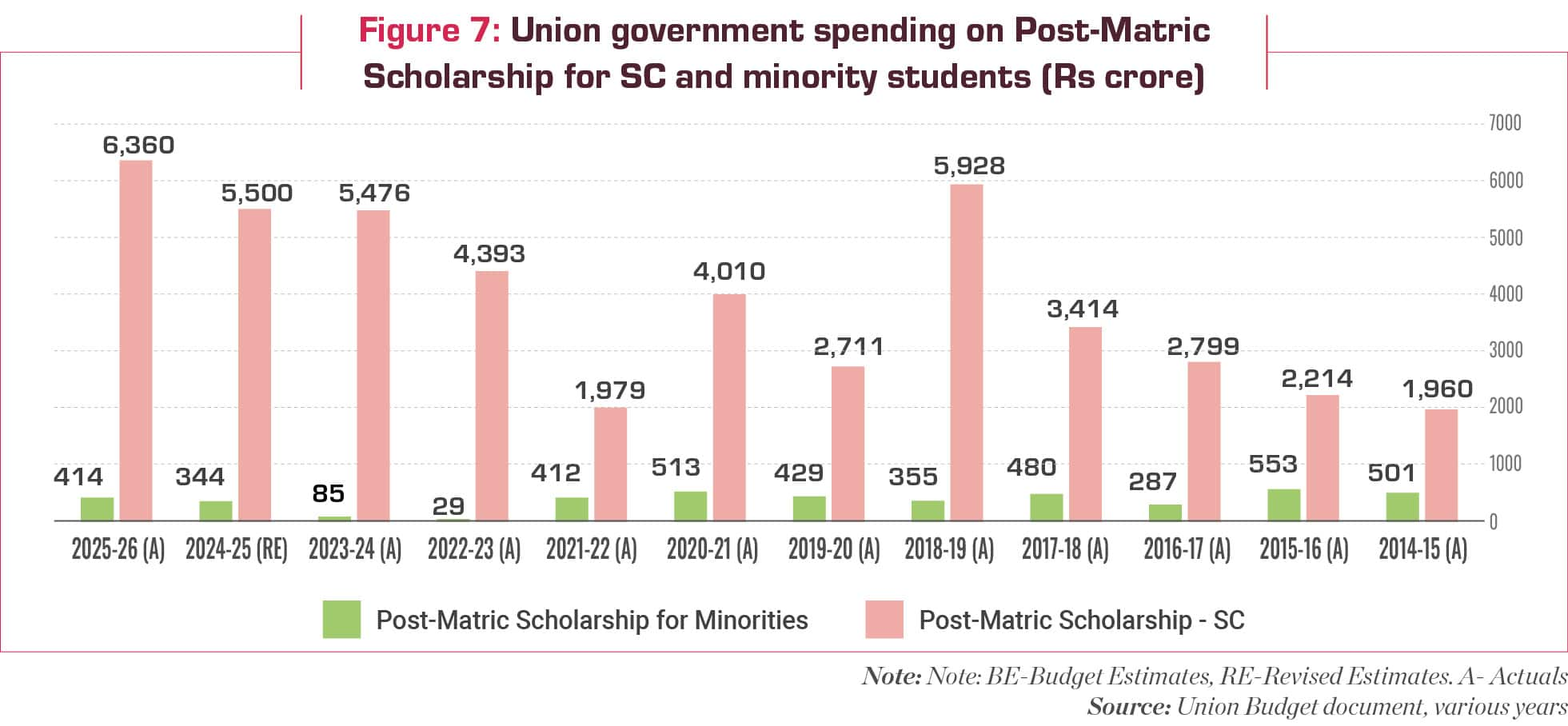

There is a declining trend in UGC-supported fellowships; gaps between scholarship demands and disbursals are widening, especially for minority and SC-ST students (Figure 7).

Decline in trend in spending on scholarships for SC, minorities

Decline in trend in spending on scholarships for SC, minorities

The lack of robust data transparency around fellowship distribution and delays in payment disbursement further hinder students’ ability to persist in education, particularly at postgraduate and doctoral levels. This has created a situation where the burden of costs is increasingly shifting to families, risking exclusion of the very groups NEP seeks to empower.

Between 2018 and 2023, over 13,600 students from SC, ST, and OBC communities dropped out of Central Universities, IITs, and IIMs. Suicide data from central institutions is equally alarming — 122 student suicides between 2014 and 2021, with 55% from marginalised backgrounds. These figures point to systemic exclusion, insufficient support structures, and an alienating academic culture in elite institutions.

Rising dependence on education loan

Student loans are increasingly seen as an alternative source of financing higher education, particularly for credit-constrained students who may lack access to upfront funds. According to Indian Bank Association data, shared with a parliamentary standing committee, education loans were sanctioned to approximately 1.34 lakh applicants under the “Model Education Loan Scheme” in 2020–21. By 2024–25, this number had more than doubled, with loans sanctioned to over 2.75 lakh applicants11.

The same parliament panel also cites data from the Department of financial services which shows that the total count of loans disbursed rising from 4.53 lakh to 7.36 lakh from 2021-22 to 2023-24.

Loans disbursed to student accounts from different economic classes | |||

Annual family income of students | 2021-22 | 2022-23 | 2023-24 |

Upto Rs 4.5 lakh | 2,38,515 | 3,27,454 | 3,56,123 |

Above Rs 4.5 lakh | 2,14,949 | 3,01,994 | 3,80,457 |

Source: 364th report, Department related parliamentary standing committee on education, women, children, youth and sports

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) data shows that, as of January 2024, outstanding bank loans for education have increased by 23%, reaching Rs 1.17 lakh crore, a 15% rise in the previous 12 months alone12. The interest rates charged on education loans are higher as compared to other sectoral loans, due to which borrowers face problems while making repayments. With shrinking employment opportunities, the number of student loan defaulters has been steadily rising, contributing to an increase in non-performing assets in the education loan segment. In response, many banks have become more risk-averse, tightening eligibility criteria and limiting access to education loans. This is further impacting the access to higher education.

Financial, systemic challenges

Five years into the implementation of the National Education Policy (NEP) 2020, it is evident that while the policy’s vision is ambitious and comprehensive, its realisation is constrained by persistent financial and systemic challenges. The NEP rightly recognises the interdependence of foundational and higher education, and the need for curricular reform, teacher development, and institutional excellence. However, these goals require a coherent, adequately-funded education system — something current budgeting practices fall short of delivering.

Education financing in India continues to reflect structural issues: underinvestment, inequitable distribution of resources, and fragmentation between school and higher education sectors. Rather than enabling universality, recent trends point toward increasing exclusivity, with disproportionate financial support directed towards elite institutions and exemplary schools, often at the cost of broad-based public provisioning. This shift, alongside declining fellowships and the rising cost of higher education, threatens to widen educational disparities, especially for students from socio-economically-disadvantaged backgrounds.

While the NEP allows states and institutions flexibility in implementation, its outcome goals — such as universal school enrolment by 2030 and 50% GER in higher education by 2035 — are fixed and time-bound. Without substantially enhanced public investment and greater alignment between central and state efforts, these goals are unlikely to be met.

The path forward demands a recalibration of financing priorities — one that restores equity, expands public provisioning, and ensures that reforms reach all learners, not just a privileged few.

Protiva Kundu is an economist based in Delhi with an interest in education financing. This piece first appeared in the 200th issue of the Careers360 magazine, published in August 2025.

End notes:

- Ministry of Human Resource Development, National Education Policy 2020.

- Dept. of Higher Education (2024). Analysis of Budgeted Expenditure on Education, 2019-20 -2021-22

- UNESCO data base, accessed as on 20 th July, 2025

- Economic Survey, 2024-25, Ministry of Finance

- UDISE+2023-24

- Kundu, Protiva (2025). Four years of National Education Policy 2020: Reviewing the financial commitments of governments towards school education (unpublished), CBGA-CRY.

- Moneycontrol (July 15, 2025), Delhi university faces Rs 462 crore deficit amid rising student fees and UGC grant shortfall

- University Grants Commission, Annual Report, 2023-24

- HEFA portal, accessed as on 20th July, 2025

- Revitalising Infrastructure and Systems in Education by 2022, an initiative launched by Govt. of India in 2018-19 Union Budget

- Rajya Sabha (2025). Department related parliamentary standing committee on education, women, children youth and sports, Department of Higher Education, Report no 364

- Unnikrishnan, Dinesh (March 11, 2024). Banks fret over surge in education loans and rising layoffs, Moneycontrol

Correction: Figure 7 says '(A)' meaning 'Actuals' for 2025-26 allocations where it should have said 'BE' for Budget Estimates'. The error is regretted.

Follow us for the latest education news on colleges and universities, admission, courses, exams, research, education policies, study abroad and more..

To get in touch, write to us at news@careers360.com.

Next Story

]Just 30% agriculture university graduates get jobs; campus placements ‘in name only’, say BSc students

While enrolment in agriculture courses has doubled, NIRF 2025 data shows IARI Delhi, BHU, Pantnagar University getting fewer job offers; graduates study further or wait for government posts

Musab Qazi